Head Neck tumors - When to think of malignancy

Look for red flags

Frank Pameijer

Radiology Department of the University Medical Centre, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Benign head neck tumors are common, while malignant tumors

are rare.

The question is, when do we need to think of a malignant

tumor, since many radiologists will not frequently be confronted with a

malignant tumor.

In this article we provide you with some red flags, that may help

you to recognize the occasional malignant lesion in daily practice.

Introduction

In the table you will find the red flags, that makes the lesion suspicious for malignancy, although there are exceptions where benign lesions may also show red flags.

More red flegs means more suspicious.

We will discuss all these items in the next chapters.

Growth pattern

The table shows the different etiologies between lesions with a destructive versus an expansile pattern

A destructive growth pattern means full thickness break of mineralized bone.

This is most frequently seen in malignant tumors, but also in aggressive benign tumors and inflammation.

Expansile growth pattern means that there is a balance between the activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts.

This is less frequently seen in malignant lesions, but common in benign neoplasms and chronic inflammation.

Mucocele

These images are of a 47-year old male, who complained of tension in his forehead.

First look at the images.

What are the findings?

Is the lesion expansile or destructive or both?

Then continue reading...

Findings:

- Expansile lesion which displaces the left eye laterally.

- The lesion has sharp borders.

- The lesion originates in the left frontal sinus.

- Thinning of the left medial orbita wall (black arrowhead) and of the skull base (white arrowhead), but no destruction.

MRI was performed to confirm the most likely diagnosis of a mucocele...

The MRI shows an expansile lesion with only rim enhancement.

There is no enhancement within the lesion.

This confirms the diagnosis of a mucocele.

A mucocele is a cystic lesion filled with mucous.

It develops when the opening of (part of) a paranasal sinus

becomes obstructed.

Scroll through the MRI images.

Here more examples of mucocele.

- Small mucocele

in the sphenoid sinus.

There is complete fill with soft tissue (i.e. mucus) as well as expansion with intact bony margins of the sinus. - Frontal sinus mucocele.

Sometimes, thinning of the bony margin is present simulating destruction. On thin CT-slices it is usually possible to see the intact bony structure. - Mucocele of an anterior ethmoid sinus cell.

- Right sphenoid sinus mucocele. The intersphenoidal septum is expanded over the midline.

- Frontal sinus mucocele.

- Mucocele of the right ethmoid sinus with thinning and expansion of the lamina papyracea into the ipsilateral orbit.

Mucocele versus Retention cyst

In order to fulfill the criteria for mucocele, there has to be both complete fill-in as well as expansion of a sinus.

Image

This patient has a mucocele in the left maxillary sinus with

a little bit of expansion (white arrow).

On the right there is a mass without expansion (yellow

arrowhead) and there is still some air in the maxillary sinus.

This is a retention cyst.

Image

This patient also has a mucocele in the left maxillary sinus.

On the right there is a complete fill in of the maxillary sinus, but no expansion .

Therefore it does not fullfill the criteria for the diagnosis of a mucocele.

The most common site of a mucocele is the lower lip.

Other

locations include the oral cavity.

If the lesion originates from the obstructed

sublingual gland, it is called a ranula.

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma

These images are of a 75-year old male who complains of a stuffy nose and bleeding from the nose.

First look at the images.

Continue with the coronal reconstructions...

Scroll through the images.

What are the findings?

Is the lesion expansile or destructive (red flag)?

Is there another red flag?

Then continue reading...

The two red flags are:

- Destruction of the medial wall of the maxillary sinus (black arrow) and of the nasal septum (white arrow).

- The disease is purely

unilateral.

In patients with rhinosinusitis there may be expansion and even sometimes bony destruction, but the disease is (almost) always bilateral.

Continue with the MRI...

On these STIR-images you can see the difference in signal intensity between the obstructed maxillary and ethmoid sinuses (black arrows) and the tumor (white arrows).

In patients with a mucocele the entire lesion would have had the same signal intensity unlike this case.

On the diffusion images the lesion has a high signal

intensity on b1000.

On ADC, the lesion has a very low signal intensity, even

lower that brain tissue, indicative of marked restriction.

This means that we

are dealing with a hypercellular tumor.

This is a third red flag.

On the CT you might get the impression that the tumor also involves the frontal sinus (black arrow).

However on the MRI we can clearly see that the frontal sinus is only obstructed and has a higher signal intensity (white arrow) compared to the tumor in the ethmoid sinuses (yellow arrows).

The final conclusion is:

- Malignant tumor in the right nasal cavity with involvement of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses.

- No involvement of the frontal sinuses and no invasion intracranially.

- Destruction of medial wall of maxillary sinus and septum.

Biopsy showed a sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC), which has a very poor prognosis.

The patient was treated with resection and post-operative radiotherapy and to our surprise there is no sign of recurrence after four years.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Here another example of a lesion with a destructive growth

pattern.

Notice the tumor enhancement on the MRI (arrow).

There is invasion of the (medial) orbit.

Biopsy showed a squamous cell carcinoma.

Localization

In the nasal cavity and the paranasal sinuses the most common diseases are sinusitis and polyposis.

These diseases are almost always bilateral.

Any disease which is unilateral, should raise the question: could this be a malignant tumor?

Adenocarcinoma

This is a patient who complains of obstructive nasal congestion.

Now, if you would only report this case as subtotal opacification of the paranasal sinuses on the right, the treating physician could would be inclined to think, that it is (just another case of) ordinary sinusitis.

As we have discussed before, the red flag here is the

unilateral localization of the abnormality.

A unilateral sinusitis is extremely uncommon.

and if you look carefully, there is destruction of the nasal

septum, which is a second red flag.

Continue with the MRI...

The MRI-images show a unilateral tumor in the right nasal cavity with obstruction of frontal sinus and to a lesser degree also of the maxillary sinus.

There is diffusion restriction (high on DWI and low on ADC), which is the third red flag.

Biopsy revealed an adenocarcinoma.

The patient was treated with resection followed by proton radiation and is now disease-free for 14 months.

Inverted papilloma

Here another unilateral tumor.

The enhancing tumor has a higher signal intensity compared to the obstructed maxillary sinus.

Notice that the tumor has a lobulated border.

This is frequently seen in inverted papillomas, but is not highly specific and anyhow a biopsy has to be performed.

Final diagnosis: inverted papilloma.

This is another inverted papilloma.

It presents as a lobulated mucosal mass with a ‘cerebriform’ appearance.

As if we are looking at gyri (arrowheads).

This finding is somewhat specific for inverted papilloma

Next to a malignant lesion, another cause of unilateral paranasal obstruction has to be kept in mind.

This is illustrated in this case.

This is a 62-year old female patient.

CT sinus was requested by the otolaryngologist. Clinical information: ‘chronic unilateral sinusitis’.

Images

There is a soft tissue obliteration of the right maxillary, ethmoid and frontal sinus (a so-called ‘infundibular pattern’).

As discussed above, this is a red flag.

Look at the following images and try to decide if there is a malignant lesion causing the infundibular pattern (or is there another cause?)

Images

There are periapical lucencies around the roots of a right upper molar indicative of dental infection (black arrowheads).

Compare to the normal left side on the axial image (white arrowhead).

Further clinical examination excluded a malignant lesion.

The patient was referred for dental evaluation because a dental infection may well be the cause of a unilateral chronic sinusitis.

Note: For this reason, it is crucial to include the maxilla in the field of view of a sinus CT.

Vascularization

As a single feature,

vascularity is not very specific in the discrimination between benign and

malignant in head and neck tumors.

But in combination with other imaging

features, it can be quite helpful in the differential diagnosis.

Think of the strong enhancement and flow voids on MR in glomus tumors (paragangliomas) in combination with the localization (i.e. from the carotid bifurcation up to the jugular foramen).

In any vascular lesion in the head-neck region we should check:

- Dilated feeding or draining vessels.

- Doppler flow pattern

- Flow voids on MR

- Phleboliths on CT

- Doppler flow pattern on ultrasound

Rhabdomyosarcoma

These images are of a 16-year old male with proptosis and nasal bleeding.

First study the images.

Look for red flags.

Then continue reading.

Based on the CT examination in another hospital there was a

suspicion of a juvenile angiofibroma, which is a hypervascular locally

aggressive tumor in young males with severe nasal bleedings, that can be

life-threathening.

On these images there is a destructive lesion with invasion

of the orbita.

A juvenile angiofibroma always originates from the posterior nasal cavity and is centered around the sphenopalatine foramen and pterygopalatine fossa.

Continue with the additional images...

Pterygopalatine fossa

The pterygopalatine fossa is an inverted pyramidal-shaped, fat-filled space located on the lateral side of the skull, between the infratemporal fossa and the nasopharynx.

It is a major neurovascular crossroad between the orbit, the nasal cavity, the nasopharynx, the oral cavity, the infratemporal fossa, and the cranial fossa.

Given its connections, the pterygopalatine fossa can act as a conduit for the spread of inflammatory and neoplastic diseases in the head and neck.

These images are of two different patients.

- This is a patient with a squamous cell carcinoma originating in the right maxillary sinus, that infiltrates the pterygopalatine fossa (red arrow).

Notice normal fat in the left pterygopalatine fossa (yellow arrow). - This is our

16-year old male.

Notice that the fossa is not involved and that the center of the lesion is not in the sphenopalatine foramen and pterygopalatine fossa.

This made the original diagnosis of a juvenile angiofibroma unlikely.

Continue with the MR-images...

The MRI shows a unilateral destructive tumor with marked diffusion

restriction (low signal intensity on ADC).

So we have three red flags.

The diffusion restriction is another argument against the diagnosis of an juvenile angiofibroma, because a vascular lesion would not cause diffusion restriction.

There is invasion of the orbit and also of the anterior soft tissue of the cheek (arrow).

A biopsy was performed which revealed a rhabdomyosarcoma, which was treated with chemotherapy.

Juvenile angiofibroma

First look at the images.

Why is this a typical juvenile angiofibroma?

Findings:

- The tumor is located posteriorly in the nasal cavity and the center is around the expected location of the sphenopalatine foramen (asterix).

- There is strong enhancement with a little bit of "salt and pepper" appearance.

Continue with the DSA...

The DSA shows the hypervascularity, which (in combination with the characteristic localization) is strongly indicative of juvenile angiofibroma.

Pre-operatively this patient was treated with embolization.

Surgery has to be as radical as possible in order to prevent

recurrence.

First look at the images.

What are the findings?

Findings:

- Tumor centered around the right sphenopalatine fossa.

- There is expansion of the pterygopalatine fossa, but no destruction.

- Even on CT we can see the marked enhancement

This is a typical juvenile angiofibroma.

Continue with the MRI and DSA...

And again the typical findings on MRI and DSA.

There is strong

enhancement and hypervascularity.

Cystic lesion in the neck

Cystic lesions in the neck are very common.

In young patients the chance of malignancy is low.

However a cystic lesion in an adult patient, especially when

over 30 years, is a red flag.

Branchial cleft cyst

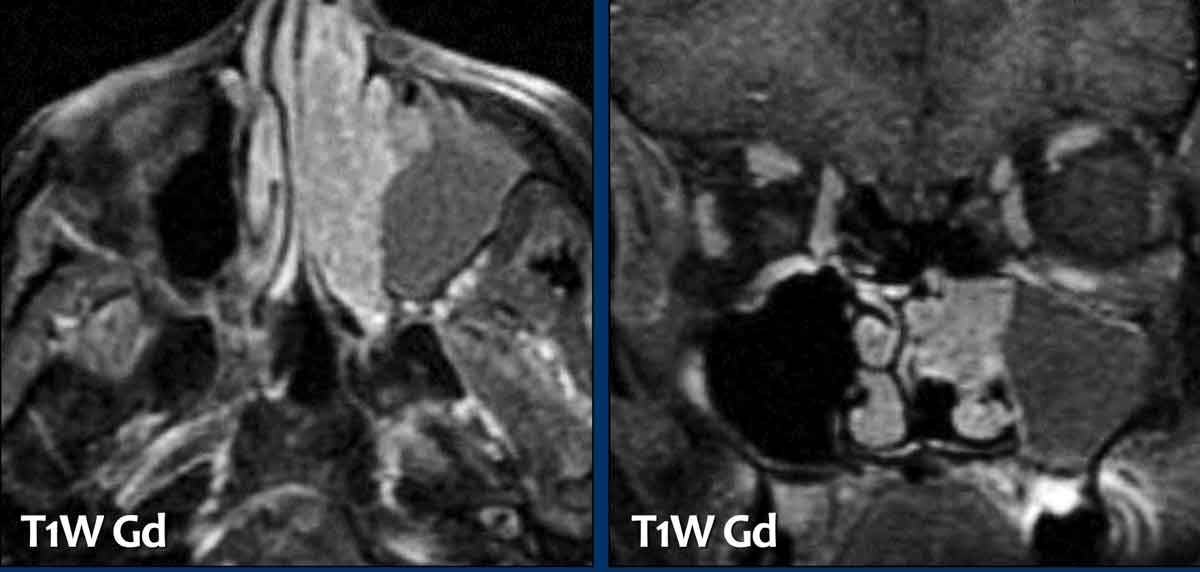

These images are of a 59-year old man, who is a smoker and presents with a swelling in the neck.

The original MR-report stated that there was a cystic lesion

posterior to the submandibular gland and anterior to the sternocleidomastoid

muscle; no associated lymphadenopathy.

Most likely diagnosis: branchial cleft

cyst.

This seems a logical conclusion since the typical location of

a (second) branchial cleft cyst is between the submandibular gland and the

sternocleidomastoid muscle.

However the age of the patient is a red flag.

Continue reading...

Five months later the swelling became painful.

The MRI is repeated.

Look at the images.

What is your diagnosis?

The findings are:

- There is some enhancement of the wall and in the surrounding soft tissues.

- No diffusion restriction.

These findings were thought to be the result of infection and a cystic metastasis was less likely, but could not be excluded, especially because of the age of the patient.

The patient was treated with antibiotics and one month later the lesion was excised.

The specimen proved to be a branchial cleft cyst.

Typical branchial cleft cysts are thin walled cystic lesions.

However, cystic metastases can mimic a branchial cleft cyst.

Especially lymph node metastases of a papillary thyroid

carcinoma and of an (HPV associated) oropharyngeal carcinoma.

Human papilloma virus is the cause of cervical cancer and is associated with vaginal and vulvar cancer

It is also associated with cancer of the oropharynx (back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils).

As a rule of thumb: Any cystic neck lesion in an adult patient, especially when over 30 years, should be considered suspicious and a malignant origin should be excluded.

This is a branchial cleft cyst in a ten-year old in the typical location.

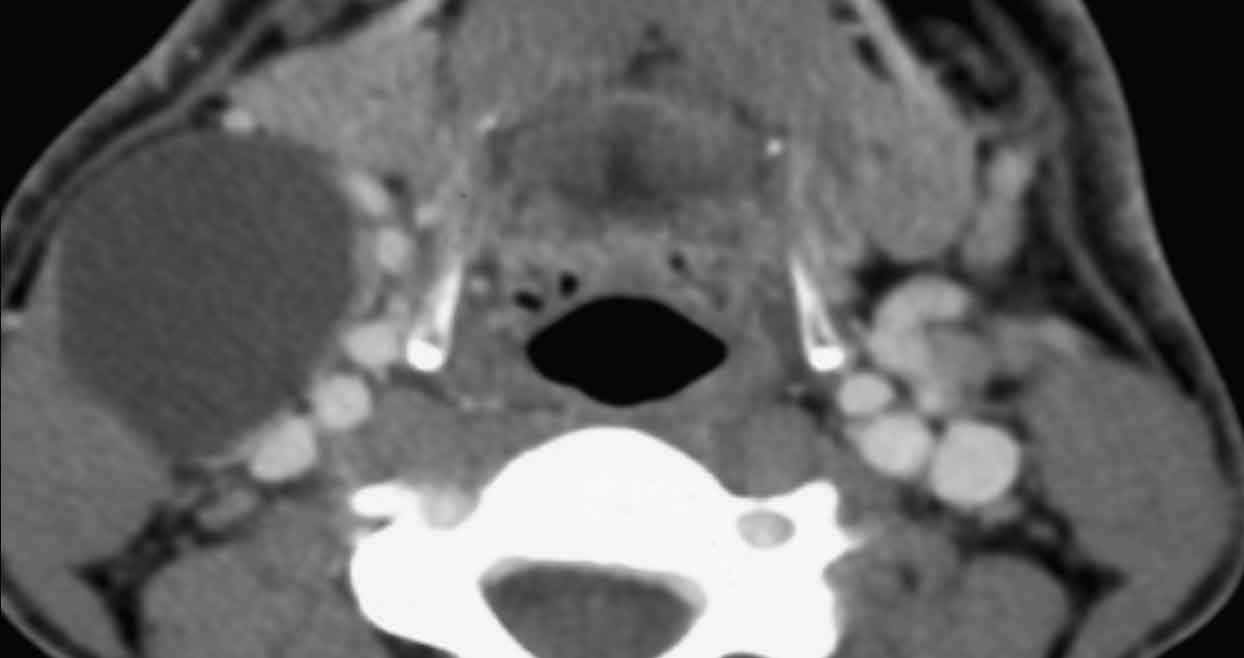

HPV associated oropharynx carcinoma

These images are of a 69-year old man with a left neck swelling.

It was reported as brachial cleft cyst.

The fluid fluid level (arrowhead) was thought to be debris as a result of prior infection or bleeding.

In the follow up the swelling increased and ten months later the lesion was excised.

Pathology: Metastasis of a squamous cell carcinoma, positive for P16 marker.

This is a marker for human papilloma virus positivity.

Continue...

In search of the primary tumor, the ENT specialist noticed a slightly larger tonsil on the left.

Notice that the area of low signal on the ADC is smaller that the area of high signal on the DWI (b1000).

This means that only the center of the tonsil is cancer. The carcinoma lies deep within the crypts of the tonsil and is frequently not visible during endoscopy.

Biopsy revealed a HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma and the patient was treated with radiotherapy.

Here two more cases of (seemingly) identical lesions:

- This was a branchial cleft cyst (Case courtesy B.M. Verbist, Leiden)

- This was a lymph node metastasis of a papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Notice the nodular enhancement in the wall (arrow).

This is never seen in a branchial cleft cyst.

Conclusion

MRI Protocol

Tips

- When you notice something ‘odd’ on a so-called routine scan of head and neck (especially if you have red flags) don’t hesitate to mention the possibility of a malignant lesion in your conclusion.

- But…, be humble in suggesting a histological diagnosis.

- The otolaryngologist can usually reach the lesion and excise lesions or take a biopsy.

- The pathologist, subsequently, will make the diagnosis.

Reporting

This standard report is applicable to any head and neck tumor.

In

the description of local spread we recommend using nomenclature and landmarks

that are also used by otolaryngologists and head-neck surgeons.