Sella Turcica and Parasellar Region

Walter Kucharczyk and Marieke Hazewinkel

Radiology department of the University of Toronto, Canada and the Radiology department the Medical Centre Alkmaar, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

This review is based on a presentation given by Walter Kucharczyka and was adapted for the Radiology Assistant by Marieke Hazewinkel.

In this review a systematic anatomic approach to differential diagnosis of a sellar or parasellar mass is described.

By clicking on one of the subjects in the list on the left, you will go directly to this item.

If you have printing problems with the margins of the document, you may have to adjust the margins in the page set up of your internet browser, which you will find in the top left of the menu bar.

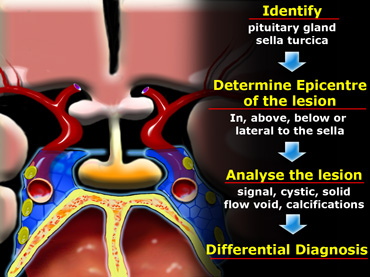

Anatomic Approach to Differential Diagnosis

In order to analyze a sellar or parasellar mass on MRI we use the following anatomic approach:

- First identify the pituitary gland and sella turcica.

- Then determine the epicenter of the lesion and whether it is in the sella or above, below or lateral to the sella.

- If it is in the sella, determine whether or not the sella is enlarged.

- Once the location of the mass is clear, analyze the signal intensity patterns: is the lesion cystic or solid?

- Does it contain any abnormal vessels?

- Are there any calcifications? And so on.

- Finally establish a Differential Diagnosis.

Pituitary gland

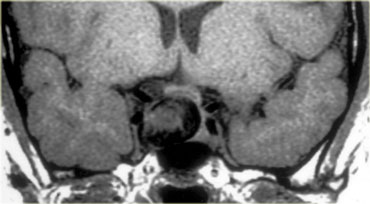

On a coronal section through the brain the reference structure is the pituitary gland which lies in the sella turcica.

It is usually larger in females than in males - in females the superior border tends to be convex, whereas in males it is usually concave.

The most common abnormalities that arise in the pituitary gland are pituitary adenoma, Rathke's cleft cyst and craniopharyngioma.

Pituitary stalk

The next structure to identify is the pituitary stalk.

This is a vertically oriented structure which connects the pituitary gland to the brain.

It is thinner at the bottom and thicker at the top.

Embryologically, it is also derived from Rathke's cleft epithelium and therefore the pathologies, which can arise in the pituitary gland can also arise in the stalk.

There are a few unusual things to be considered in children, such as germinomas and eosinophilic granulomas.

In adults metastases and occasionally lymphoma can arise in the pituitary stalk.

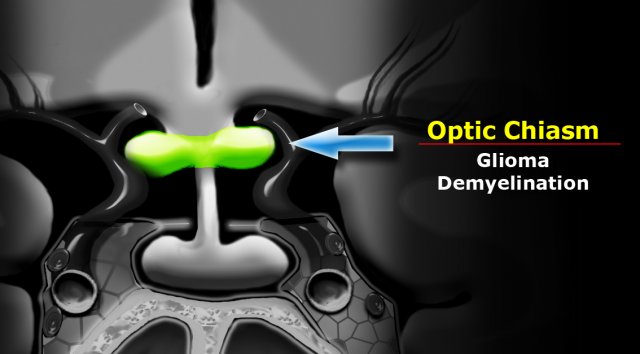

Optic chiasm

Another major structure in the suprasellar cistern is the optic chiasm.

It is an extension of the brain and looks like the number 8 lying on its side.

It is glial tissue - therefore the most common tumors to originate here are gliomas.

In the US and Europe another frequent pathology in this region is demyelinating disease - particularly multiple sclerosis.

This can also be associated with some swelling of the optic chiasm.

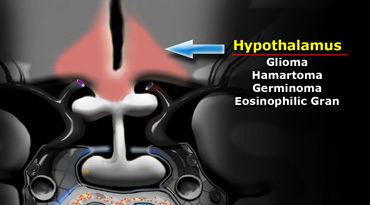

Hypothalamus

Further cephalad lies the base of the brain, which at this location is the hypothalamus.

Anatomically the hypothalamus forms the lateral walls and floor of the third ventricle.

The most common pathologies to arise here are gliomas - in children hamartomas, germinomas and eosinophilic granuloma.

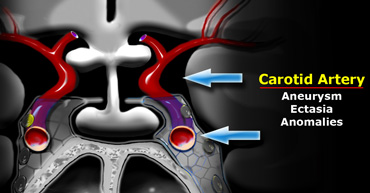

Carotid artery

A very important structure in this area is the internal carotid artery.

It runs a complex anatomic course as it passes through the skull base shaped like an S on lateral views.

It passes through the cavernous sinus.

The segment cranial to this is known as the supracavernous segment.

This bifurcates into the anterior cerebral artery, which passes cranially to the optic chiasm, and the middle cerebral artery, which runs laterally.

Aneurysms and ectasias are pathologies that can arise here.

One must also be aware of congenital variations in the course of the internal carotid

Sometimes it is very medially positioned and can actually lie in the midline.

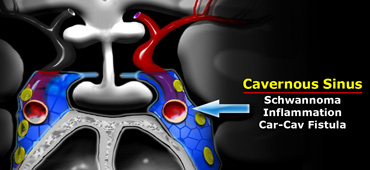

Cavernous sinus

The cavernous sinus is a paired complex of venous channels.

In the lateral wall of the sinus run nerve III (oculomotorius), IV (trochlearis), V1 and V2 (trigeminus).

The sixth cranial nerve (abducens) runs more medially and is located caudal to the carotid artery.

The most common pathologies occurring in the cavernous sinus include schwannomas arising from the cranial nerves and inflammation, which can lead to thrombosis.

This is known as cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis.

Carotid-cavernous fistulas are fistulous communications between the carotid artery and the veins of the cavernous sinus.

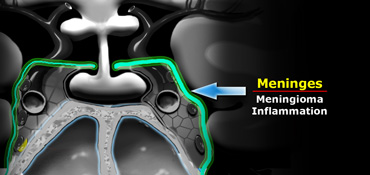

Meninges

The meninges cover the cavernous sinus.

They are thicker laterally and superiorly than medially and inferiorly.

The most common tumor to arise from the meninges is of course the meningioma.

Dural metastasis is the second most common tumor to arise here.

Also inflammatory pathologies occur in the basal meninges - the most common infection being tuberculous meningitis.

Of the non-infectious inflammatory pathologies sarcoidosis is the commonest.

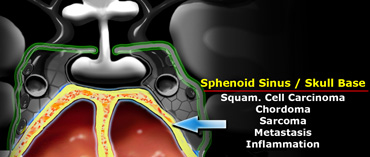

Sphenoid sinus

Inferior to the pituitary gland lies the sphenoid sinus.

This structure contains air and is lined by mucosa and bone.

Posterior to the sphenoid sinus lies the clivus (not shown on this coronal section through the brain).

Pathology that arises in this area includes carcinomas arising from the mucosa of the sphenoid sinus - squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma are the most common.

Chordomas arise in the clivus and chondrosarcomas and osteosarcomas also occur in this area.

Metastases can occur anywhere.

Bacterial or fungal inflammatory processes in the sphenoid sinus can spread intracranially via the cavernous sinus.

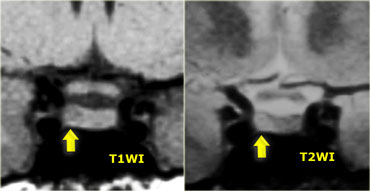

Pituitary Microadenoma

By definition, pituitary microadenomas are less than 10 mm in diameter and are located in the pituitary gland.

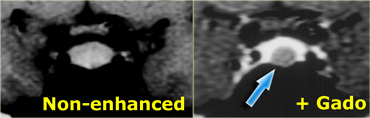

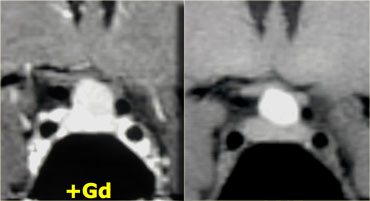

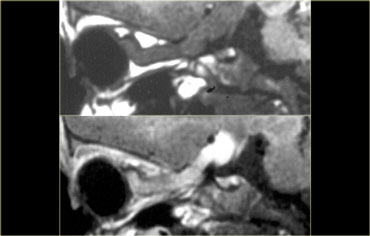

These images show a classic case: on T1 a lesion about 3-4 mm in diameter, slightly hypointense compared to normal pituitary tissue, located in the pituitary gland.

On T2, the lesion is slightly hyperintense.

The differential diagnosis: pituitary microadenoma or Rathke's cleft cyst (the two can be indistinguishable).

The sensitivity of an unenhanced MRI scan for detecting pituitary microadenomas is about 70%.

It is not always necessary to give intravenous contrast for detecting pituitary microadenomas as patients with a negative scan generally receive the same symptomatic treatment as patients with a microadenoma (usually these patients are women with symptoms of hyperprolactinemia).

The purpose of the scan is to rule out any large lesions.

In possible surgical candidates (for example patients with failed medical therapy or pituitary disease not amenable to medical therapy such as Cushing's disease) it is necessary to give contrast to localize the lesion as accurately as possible.

On an unenhanced scan, approximately 70% of all pituitary microadenomas can be detected.

If you give gadolinium, you can reduce the false-negative rate from 30% to 15%.

As mentioned earlier, this usually does not affect patient management.

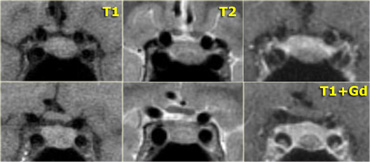

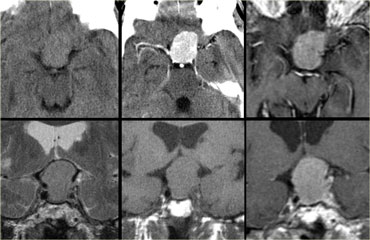

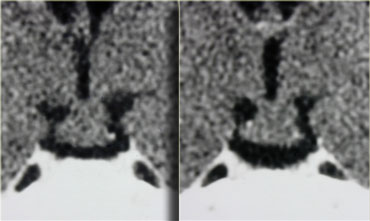

Coronal T1 and T2-weighted images and T1-weighted images before and after gadolinium.

In this patient the lesion in the pituitary gland is only detectable after the administration of intravenous contrast.

The differential diagnosis: pituitary microadenoma or Rathke's cleft cyst.

Pituitary Macroadenoma

By definition, pituitary macroadenomas are adenomas over 10mm in size.

They tend to be soft, solid lesions, often with areas of necrosis or hemorrhage as they get bigger.

As they grow, they first expand the sella turcica and then grow upwards.

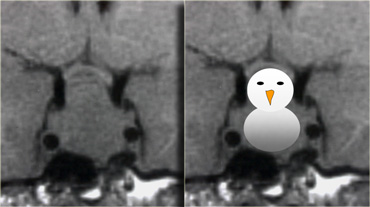

In this example of a pituitary macroadenoma there is suprasellar extension with elevation and compression of the optic chiasm.

Because they are soft tumors, they usually indent at the diaphragma sellae, giving them a 'snowman' configuration.

This is one feature that can help distinguish between a pituitary macroadenoma and a meningioma.

Another feature which can help differentiate them is enlargement of the sella turcica - this generally only occurs with pituitary macroadenomas that originate in the sella.

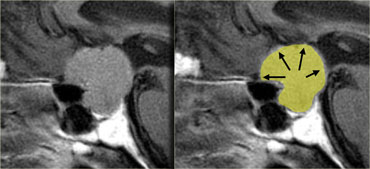

On the left another example of a pituitary macroadenoma.

The lesion starts in the sella, which is enlarged, and extends into the suprasellar cistern.

Note the classic 'snowman' configuration caused by constriction by the diaphragma sellae.

Notice the blood-fluid level, indicating hemorrhage.

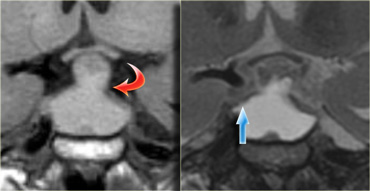

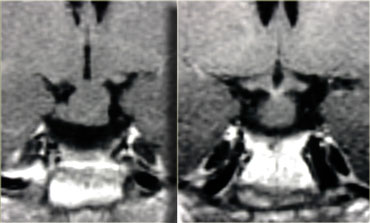

The usefulness of observing the inclination of the diaphragmatic leaflets was referred to earlier.

On the T2-weighted images on the right you can see that the leaflets are displaced upwards by this macroadenoma which started in the sella and is growing upwards.

A lesion originating above the sella and growing downwards would push the leaflets in the other direction (this can be seen with meningiomas for example).

Usually the diagnosis of a macroadenoma is straightforward.

Sometimes a meningioma can give a similar appearance.

On the left an example of a meningioma.

Note there is no diaphragmatic constriction and there is uniform enhancement after the administration of intravenous gadolinium which is typical of meningioma.

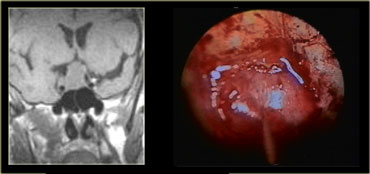

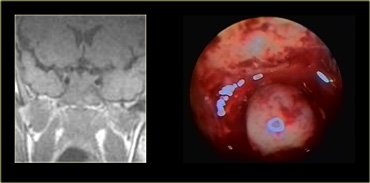

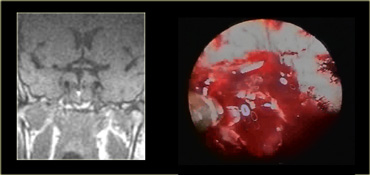

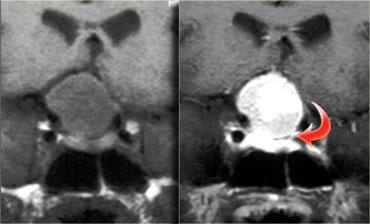

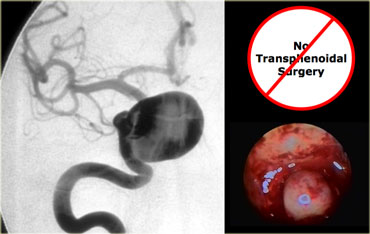

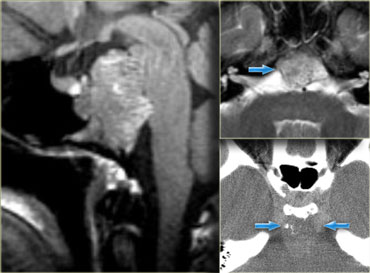

These images are of a transsphenoidal resection of a pituitary macroadenoma.

After the bony floor of the sella turcica has been removed, the dura is incised with a cruciate incision.

Because the pressure above the dura is larger than the pressure below, the macroadenoma then delivers itself into the sphenoid sinus.

Intra-operative MRI was performed in an experimental setting to determine whether the neurosurgeon had successfully removed all of the tumor.

Because using this surgical approach means a limited field-of-view, it is important to know beforehand what it is you are operating on.

As we will see there are lesions you do not want to operate using this approach!

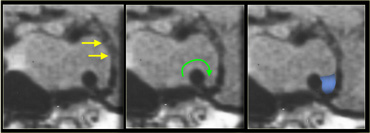

Another common pathway of extension is laterally into the cavernous sinus.

It is not always possible to tell if there is cavernous sinus invasion, but there are three signs to look out for:

-Is there more than 50% encirclement of the carotid artery? Note: meningiomas tend to constrict the carotid artery, macroadenomas do not.

-Is there lateral displacement of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus compared to the opposite side?

-Is there an increased amount of tissue interposed between the carotid artery and the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus?

At medical school they teach you that a rare manifestation of a common lesion is more likely than a rare abnormality.

Since pituitary adenomas are the most common lesions of the skull base, it is prudent to always include them in the differential diagnosis if you can not identify a normal pituitary gland when confronted with a mass in this region.

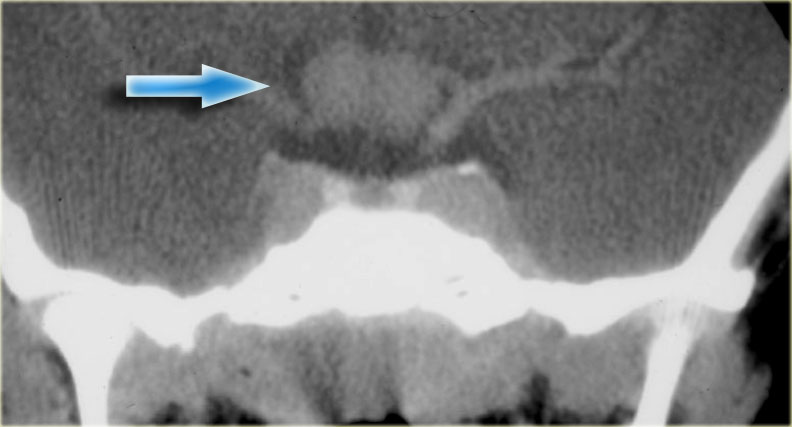

This patient presented with nasal obstruction.

She went to an ENT specialist who saw a large endonasal mass and she was referred to the neurosurgeon for planned major skull base resection.

The neurosurgeon had seen something similar before, and checked her prolactin-level.

This was 4000 (25 or less is normal). Endonasal biopsy revealed prolactinoma.

After treatment with bromocriptine the mass shrunk down and no surgery was necessary.

Rathke Cleft Cyst

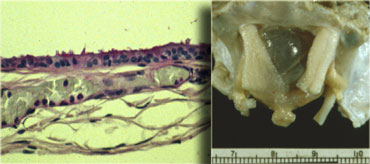

Rathke's cleft cyst is the second of three pathologies derived from Rathke's cleft epithelium.

The cyst is fluid-filled and has very thin walls with a thickness of only one or two cell layers.

This is illustrated by the microscopic image.

These walls can contain cells which secrete fluid, allowing the cyst to grow and compress adjacent structures.

Rathke's cleft cysts can occur either in or above the sella turcica.

On the images above there is a normal pituitary gland, a normal optic chiasm and a normal carotid artery on each side.

The pituitary stalk is not identifiable, however, due to a round mass in this area.

The mass has a high signal intensity on the unenhanced T1-images.

Now the only two things that are this bright on unenhanced T1-weighted images are either fluid (blood or proteinacious fluid) or fat.

Solid masses are not this bright.

Therefore it is most likely a cystic structure originating from the pituitary stalk, probably a Rathke's cleft cyst.

A cystic craniopharyngioma is also in the differential diagnosis.

These images illustrate the importance of unenhanced T1 images.

They allow you to appreciate that the abnormality is located in the pituitary stalk alone.

If you were only presented with images after the administration of intravenous contrast, you might think the pituitary gland was abnormal as well.

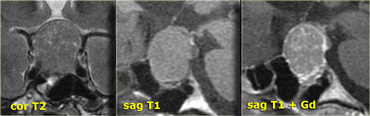

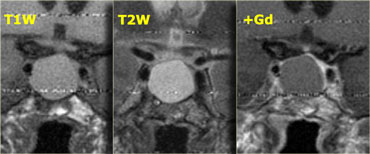

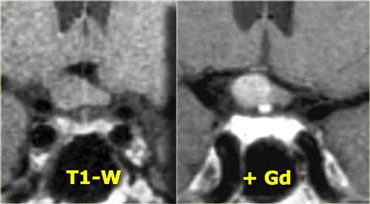

These T1, T2 and T1-weighted images after gadolinium demonstrate another Rathke's cleft cyst located in the pituitary gland.

Unlike the normal pituitary tissue and pituitary stalk it does not enhance after the administration of intravenous contrast.

The normal pituitary tissue is compressed and displaced far to the left. It is important to recognize this as it could be mistaken for an enhancing component of the cystic mass.

In general, all extra-axial masses , i.e. masses outside of the brain like the pituitary gland and stalk, will enhance because they do not have a blood-brain barrier.

If you have a non-enhancing extra-axial mass, there are three possibilities:

- Rapid arterial flow (eg. large blood vessel).

- No cellular tissue (eg. cyst).

- No blood supply (eg. infarcted mass).

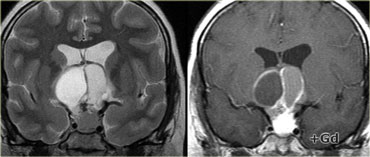

Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngioma is the third of the three pathologies derived from Rathke's cleft epithelium.

Technically these are benign tumors, but unlike Rathke's cleft cysts, they have thick walls and are locally invasive.

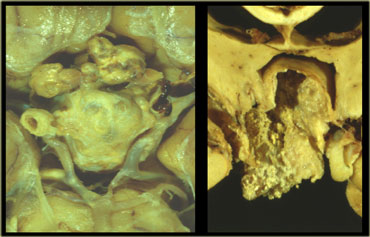

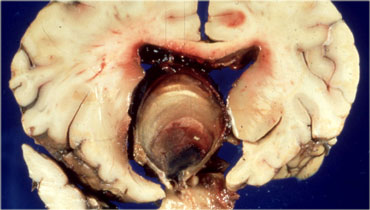

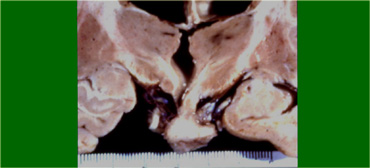

Macroscopically, it is a complex mass with multiple nodules at the base of the brain, sinuating along the fissures.

Often, it can not be completely resected.

The picture on the right shows a thick-walled cyst as part of the craniopharyngioma.

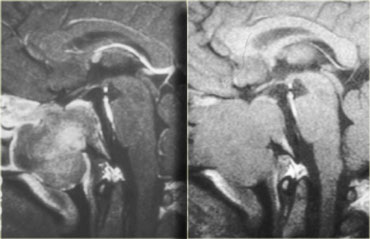

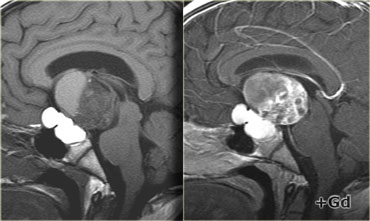

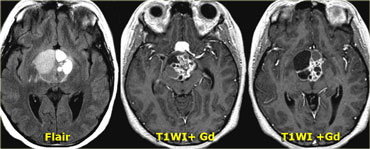

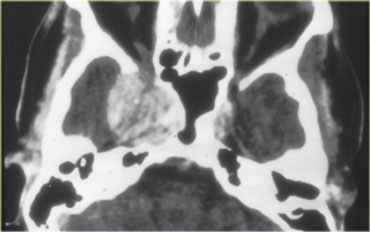

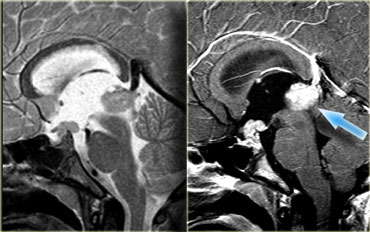

In over 50% of cases craniopharyngiomas have a pathognomonic appearance.

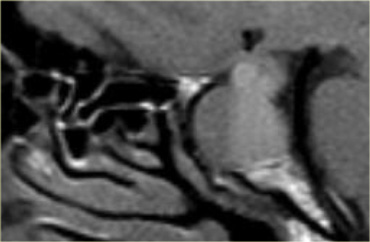

On these unenhanced and enhanced T1-weighted sagittal images, a compressed pituitary gland can be identified.

There is a large intrasellar and suprasellar mass with cystic and enhancing components as well as calcifications.

These findings in a child are virtually pathognomonic for craniopharyngioma (perhaps with only a dermoid in the differential diagnosis).

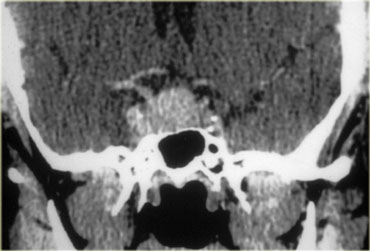

Coronal images of the same mass.

And axial images.

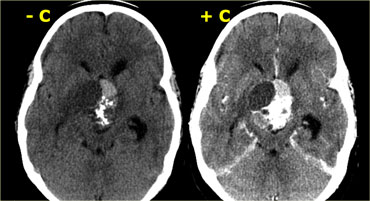

Unenhanced CT shows the calcifications more clearly.

After intravenous contrast the total extent of the lesion and its cystic components are much less evident.

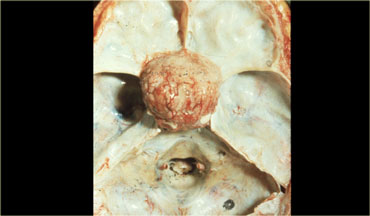

Meningioma

The most common intracranial tumor in adults is the meningioma with 20% of occurring at the skull base.

This is an autopsy specimen with the brain removed, showing a meningioma sitting on the diaphragma sellae.

Meningiomas are almost always solid lesions, sometimes with a cyst on the edge.

They can lift up the arachnoid a little bit and enhance uniformly as a general rule.

On the top-left unenhanced and enhanced CT-images, the main differential diagnosis of the enhancing mass would include meningioma, pituitary adenoma and an aneurysm.

The post-constrast MR-image on the top-right rules out an aneurysm as a possible diagnosis (no flow void), but on axial images a pituitary adenoma and meningioma are still difficult to differentiate.

Notice the spread of the lesion along the meninges.

The epicentre of the lesion is above the sella.

On the coronal images (T1 and T1-postcontrast), a compressed pituitary gland can be identified at the bottom of the sella turcica.

Above it lies a large mass, partially intrasellar and partially suprasellar.

Although the diaphragma sellae can not be identified on these images, it is probably a suprasellar mass growing downwards.

When pituitary macroadenomas get this size they usually have areas of hemorrhage or necrosis - in mengiomas this is less often the case.

Aneurysm

This is an important case to keep in mind.

This patient is a woman in her late forties, who presented to her family doctor with galactorrhea.

The family doctor did a number of tests, including a determination of her prolactin level.

This was about 150 (25 or less is normal).

Thinking the patient had a pituitary adenoma, the family doctor ordered this CT scan.

It is easy to get tunnel vision when reporting on a scan like this as a radiologist when the clinical information includes hyperprolactinemia and galactorrhea.

Of course your first thought is a pituitary adenoma.

If you look at the location of the lesion however (partially in the sella turcica and partially in the cavernous sinus), there are other possibilities, including a meningioma or an aneurysm.

The radiologist reported this as a pituitary adenoma, and the patient was treated with bromocriptine.

The bromocriptine had no effect, and the patient went to a neurosurgeon for a surgical opinion.

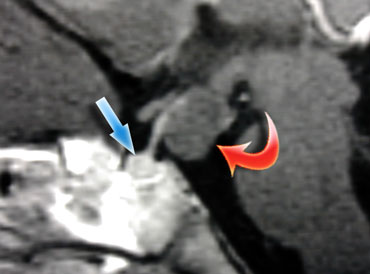

The neurosurgeon ordered this MRI.

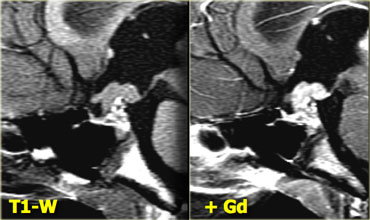

The lesion partly in the right cavernous sinus and partly in the sella turcica is predominantly black on this T1-weighted image.

In general there are three things that are black on MRI: air, bone and rapid blood flow. In this case it is black due to rapid blood flow in a carotid aneurysm.

This is the corresponding angiogram.

Obviously, this is not a lesion to be operated on transsphenoidally!

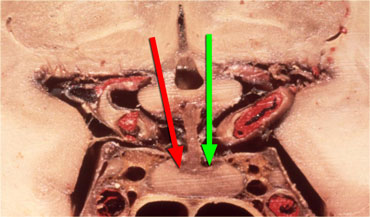

Hypothalamus hormones either stimulate (green arrow) or inhibit (red arrow) the production of pituitary hormones.

Hypothalamus hormones either stimulate (green arrow) or inhibit (red arrow) the production of pituitary hormones.

Why did the aneurysm cause hyperprolactinemia and galactorrhea in this patient?

It was caused by compression of the pituitary stalk.

The pituitary stalk connects the hypothalamus to the pituitary gland and hormones produced in the hypothalamus are transported to the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland via portal veins running along the stalk.

Most of these hormones stimulate the production of other hormones in the pituitary gland (such as TRH, GnRH, GHRH and CRH), but the release of dopamine inhibits the production of prolactin by the anterior lobe of the pituitary.

Therefore when the stalk is compressed by a mass or is transected, the level of prolactin rises while all the other hormone levels decrease.

This is known as the 'Stalk Section Effect'.

It is the reason why masses other than adenomas can cause hyperprolactinemia.

This is also why an unenhanced MRI scan suffices in a patient with hyperprolactinemia: it is not the size of the microadenoma, but ruling out other pathology that matters.

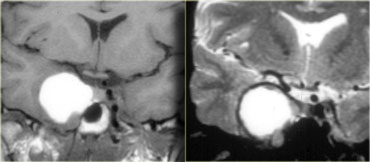

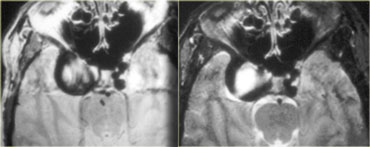

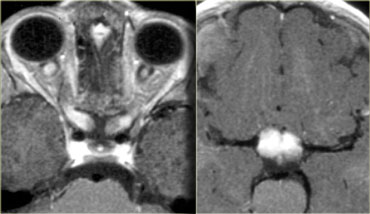

On the left the T1-weighted image of a thrombosed aneurysm with high signal intensity on the unenhanced scan.

It originates in the intracavernous segment of the right internal carotid artery.

On the right the T2-weighted images: the thrombosed aneurysm has a dark rim.

This is an example of a partially thrombosed aneurysm in the suprasellar cistern.

The patent lumen is black on these T1-weighted images.

It is surrounded by clot of different ages arranged in layers reaching from the lumen to the wall.

It resembles an onion cut in half.

On the left an autopsy specimen.

You can see that this patient suffered a massive intraventricular and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The layers of bloodclot are very nicely reflected in the MR images.

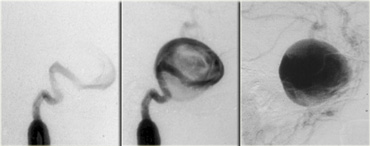

Aneurysm vs Meningioma

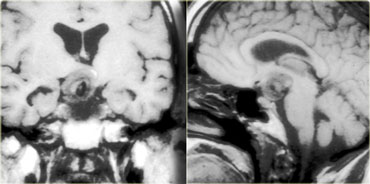

One of the most difficult differential diagnoses on CT is aneurysm versus meningioma.

In this patient there is a large mass on the right hand side, possibly originating from the meninges or cavernous sinus.

On CT it is impossible to tell whether this mass is an aneurysm or a meningioma.

This is an MRI of the same patient.

The mass is predominantly black and there is a large flow artefact running in the phase-encoding direction.

These findings correspond to rapid blood flow, and the mass must therefore be an aneurysm.

Angiogram of the same patient.

It demonstrates that the flow in the aneurysm is not laminar, but that it swirls, gradually filling the lumen with contrast.

Hamartoma

Hamartomas are masses of dysplastic tissue found almost exclusively in young children.

One of the most common locations is the floor of the third ventricle.

This is a pathology specimen showing a small nodule hanging in the suprasellar cistern.

They are benign lesions, but patients do succumb to them because of the bad location.

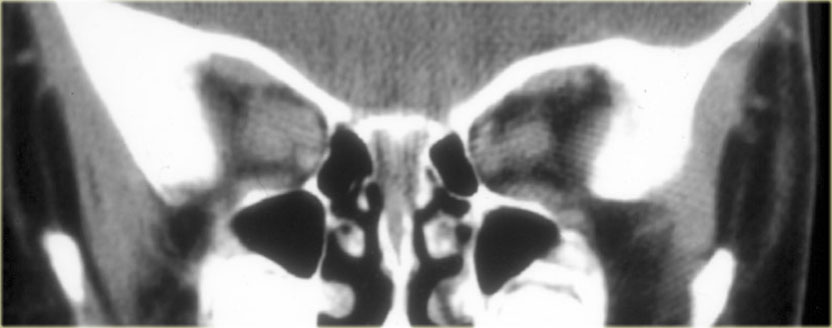

These are CT images of a hamartoma suspended from the floor of the third ventricle.

It does not enhance after the administration of intravenous contrast.

MR images of a similar small nodule suspended from the floor of the third ventricle.

The best images to see hamartomas on are enhanced sagittal T1-weighted MR images.

Here you can see the non-enhancing hamartoma attached to the tuber cinereum between the pituitary stalk and mamillary body.

There really is no differential diagnosis.

Hypothalamic and Chiasm Glioma

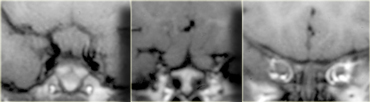

Gliomas can occur in any part of the brain and the optic chiasm is a common location, particularly in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1.

This enhanced CT shows an example of an optic nerve glioma in a patient with neurofibromatosis.

There is a suprasellar mass which is indistinguishable from the optic chiasm.

Further forward at the level of the orbits the optic nerve is abnormal on both sides.

These consecutive coronal MR-images show the mass at the optic chiasm and the swollen optic nerves.

On these axial images you can see the optic nerves and chiasm enhance after the administration of intravenous gadolinium.

The way a patient is normally positioned, slices through the nerves themselves are not obtained.

These slices can be used to make oblique images along the axis of the nerves.

With these images as a result.

Note the enhancement of the nerve after intravenous contrast with sparing of the meninges.

Approximately 25% of optic nerve gliomas do not enhance, so a lack of enhancement should not prevent you from making the diagnosis.

This is another example of a right-sided optic nerve glioma with enhancement after gadolinium.

Note the normal pituitary gland and stalk.

Germinoma

The following case concerns a 9-year-old male with a history of headache, nausea and vomiting.

Sagittal T1 images before and after intravenous contrast show a mass in the midline, on the floor of the third ventricle.

The mass enhances after gadolinium.

Continue with next images.

T2- and T1 weighted sagittal images of the same patient show a similar mass in the epiphysial area.

This is a germinoma - an intracranial germ cell tumor that occurs primarily in children and adolescents.

These are typical localisations.

These lesions crawl along the floor of the 3rd ventricle.

Chordoma

Chordomas are the most common lesions of the clivus, also a favored location for metastases and chondrosarcomas.

This patient has a normal pituitary gland.

Posterior to this is a large, fungating mass positioned at the level of the clivus.

The CT shows some calcifications in this area.

The differential diagnosis for this mass would be chordoma or chondrosarcoma.

Chordomas tend to occur in the midline, whereas chondrosarcomas tend to occur off the midline.

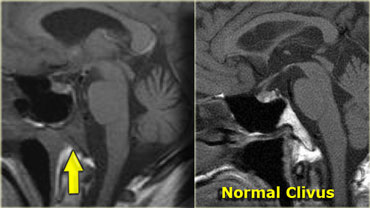

Metastases

The patient on the left is a patient with lung cancer who presented with a sixth cranial nerve palsy.

The abnormality is in the clivus, which should have a high signal intensity on this sagittal T1-weighted image (as in the image on the left).

A low signal intensity means the normal fatty marrow has been replaced by some other tissue.

In this case by tumor metastasis.

Also lymphomas, myelomas or diffuse bone abnormalities can give this appearance.

Therefore always take a minute to look at the clivus.

So again in order to analyse a sellar or parasellar mass on MRI we use the following anatomic approach:

- First identify the pituitary gland and sella turcica.

- Then determine the epicenter of the lesion and whether it is in the sella or above, below or lateral to the sella.

- If it is in the sella, determine whether or not the sella is enlarged.

- Once the location of the mass is clear, analyze the signal intensity patterns: is the lesion cystic or solid?

- Does it contain any abnormal vessels?

- Are there any calcifications? And so on.

- Finally establish a Differential Diagnosis.