Neonatal Brain US

Erik Beek and Floris Groenendaal

Department of Radiology and Neonatology of the Wilhelmina Children's Hospital and the University Medical Centre of Utrecht, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Cranial sonography (US) is the most widely used neuroimaging procedure in premature infants.

US helps in assessing the neurologic status of the child, since clinical examination and symptoms are often nonspecific.

It gives information about immediate and long term prognosis.

by Erik Beek and Floris Groenendaal

Introduction

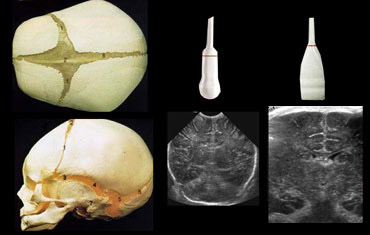

Use both the sector and linear transducer and examine the greater fontanel and if necessary also the lesser and sphenoidal fontanel.

Use both the sector and linear transducer and examine the greater fontanel and if necessary also the lesser and sphenoidal fontanel.

Ultrasound is a fast and bedside examination which makes it ideal for premature infants.

Try to get all the information you can.

Do not limit yourself to only one transducer or only one acustic window (figure).

Generally the large fontanel is used as acoustic window.

The small fontanel however is a good window to the occipital lobes.

This can be usefull in patients with borderline hyperechogenicity in these areas.

Disadvantages of US are:

- Limited overview in posterior fossa and convexity of the brain

- Absence of US-signs in ischemia in full-terms in first 24 hours

- Difficulty in detecting migration disorders, cortical dysplasia

Peri Ventricular Leukomalacia (PVL)

PVL is also known as Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) of the preterm.

It is a white matter disease that affects the periventricular zones.

In prematures this white matter zone is a watershed zone between deep and superficial vessels.

Until recently ischemia was thought to be the single cause of PVL, but probably other causes (infection, vasculitis) play an additional role.

PVL presents as areas of increased periventricular echogenicity.

Normally the echogenicity of the periventricular white matter should be less than the echogenicity of the choroid plexus.

PVL occurs most commonly in premature infants born at less than 33 weeks gestation (38% PVL) and less than 1500 g birth weight (45% PVL).

Detection of PVL is important because a significant percentage of surviving premature infants with PVL develop cerebral palsy, intellectual impairment or visual disturbances.

More than 50% of infants with PVL or grade III hemmorrhage develop cerebral palsy.

Grading PVL

PVL is graded according to the signs as listed in the Table on the left.

Regular sonographic examination is mandatory as cysts in PVL can develop as long as 4 weeks after birth (especially in prematures

Cranial ultrasonographic findings may be normal in patients who go on to develop clinical and delayed imaging findings of PVL.

A good protocol is US-examination at least once a week until discharge

?nd at the age of 40 weeks.

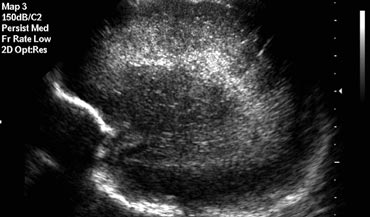

PVL grade 1

PVL is diagnosed as grade 1 if there are areas of increased periventricular echogenicity without any cyst formation persisting for more than 7 days.

Increased periventricular echogenicity is however a nonspecific finding that must be differentiated from the normal periventricular halo or normal hyperechoic 'blush' posterosuperior to the ventricular trigones.

Suspect PVL if the echogenicity is asymmetric, coarse, globular or more hyperechoic than the choroid plexus.

The abnormal periventricular echotexture of PVL usually disappears at 2-3 weeks.

PVL can be differentiated from hemorrhages because PVL lacks mass effect.

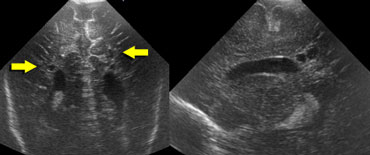

PVL grade 2

The images on the left demonstrate a PVL grade 2 with small periventricular cysts.

The echogenicity has resolved at the time of cyst formation.

2% of the preterm neonates born before 32 weeks develop cystic PVL.

The severity of PVL is related to the size and distribution of these cysts.

Cystic PVL has been identified on cranial ultrasounds on the first day of life, indicating that the adverse event was at least 2 weeks prenatal rather than perinatal or postnatal.

US is highly reliable in the detection of cystic WM injury (PVL grade II or more), but has significant limitations in the demonstration of noncystic WM injury (PVL grade I).

This deficiency of neonatal cranial US is important, because noncystic WM injury is considerably more common than cystic WM injury.

PVL grade 3

PVL is diagnosed as grade 3 if there are areas of increased periventricular echogenicity, that develop into extensive periventricular cysts in the occipital and fronto-parietal region.

PVL grade 4

PVL is diagnosed as grade 4 if there are areas of increased periventricular echogenicity in the deep white matter developing into extensive subcortical cysts.

PVL grade 4 is seen mostly in fullterm neonates as opposed to PVL grade 1-3, which is a disease of the preterm neonate.

Flaring persisting beyond the first week of life is by definition PVL garde 1.

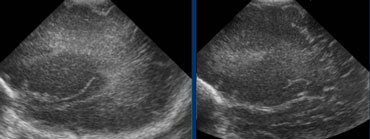

Flaring

The term flaring is used to describe the slightly echogenic periventricular zones, that are seen in many premature infants in the first week of life.

During this first week it is not sure if this is a normal variant or a sign of PVL grade 1.

Flaring persisting beyond the first week of life is by definition PVL grade 1.

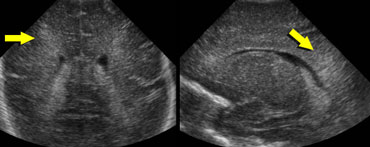

LEFT: Initial examination shows flaring.RIGHT: Follow up one week later shows normal periventricular white matter.

LEFT: Initial examination shows flaring.RIGHT: Follow up one week later shows normal periventricular white matter.

Follow up is needed to differentiate flaring from PVL grade I.

The case on the left shows a premature infant with flaring.

At follow up no cyst formation was found and after the first week a normal periventricular white matter was seen.

Germinal Matrix Hemorrhage

Germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH) is also known as periventricular hemorrhage or preterm caudothalamic hemorrhage.

These germinal matrix hemorrhages occur in the highly vascular but also stress sensitive germinal matrix, which is located in the caudothalamic groove. This is the subependymal region between the caudate nucleus and thalamus.

- The germinal matrix is only transiently present as a region of thin-walled vessels, migrating neuronal components and vessel precursors

- It has matured by 34 weeks gestation, such that hemorrhage becomes very unlikely after this age.

- Most GMHs occur in the first week of life

- Most common in infants

- These hemorrhages start in the caudothalamic groove and may extend into the lateral ventricle and periventricular brain parenchyma.

Most infants are asymptomatic or demonstrate subtle signs that are easily overlooked.

These hemorhages are subsequently found on surveillance sonography.

Grade 1 intracranial hemorrhageSagittal and coronal US of subependymal hemorrhage located in the groove between the thalamus and the nucleus caudatus.

Grade 1 intracranial hemorrhageSagittal and coronal US of subependymal hemorrhage located in the groove between the thalamus and the nucleus caudatus.

Grade 1 intracranial hemorrhage

On the left an intracranial hemorrhage confined to the caudothalamic groove.

It is staged as grade 1 hemorrhage.

In the acute phase these bleedings are hyperechoic, changing to iso- and hypo-echoic with time.

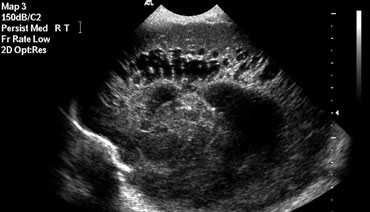

Grade 2 intracranial hemorrhage

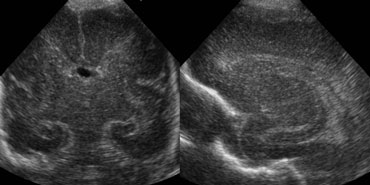

On the left a grade 2 intracranial hemorrhage.

On the coronal image only the cavum septi pellucidi is seen.

Both lateral ventricles are filled with blood, but there is no ventricular dilatation.

On the left the same patient after 3 days.

The ventricles are dilated and clot formation is seen.

Secondary hydrocephalus occuring several days after a grade 2 bleed should not be mislabeled as grade 3 hemorrhage.

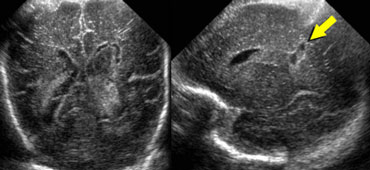

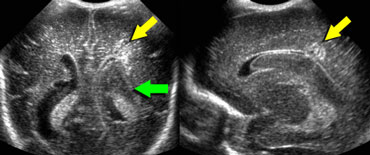

LEFT: Coronal image, green arrow indicating grade 3 hemorrhageRIGHT: Sagittal image, yellow arrow indicating venous infarction.

LEFT: Coronal image, green arrow indicating grade 3 hemorrhageRIGHT: Sagittal image, yellow arrow indicating venous infarction.

Grade 3 intracranial hemorrhage

On the left a grade 3 intracranial hemorrhage filling the left lateral ventricle.

Also note the wedge shaped hyperechoic area on the laterosuperior side of the ventricle.

This represents a small venous infarction.

Same patient as above.

Two weeks later the venous infarction has developed into a hypoechoic area with cyst formation.

Grade 4 intracranial hemorrhage

Originally these grade 4 hemorrhages were thought to result from subependymal bleeding into the adjacent brain.

Today however most regard these grade 4 hemorrhages to be venous hemorrhagic infartions, which are the result of compression of the outflow of the veins by the subependymal hemorrhage.

On the left a grade 4 hemorrhage.

There is a large subependymal bleeding but also a large area with increased echogenicity in the brain parenchyma lateral to the ventricle.

This is probably the result of a venous infarct.

These venous infarctions resolve with cyst formation.

These cysts can merge with the lateral ventricle, finally resulting into a porencephalic cyst.

On the left a different patient with a grade 4 hemorrhage at a later stage with extensive cyst formation.

Grade 1 and 2 bleeds generally have a good prognosis.

Grade 3 and 4 bleeds have variable long-term deficits, but outcome in grade 3 hemorrhages is usually good when no parenchymal injury has occurred.

Hydrocephalus is a common complication and many infants require ventriculoperitoneal shunting.

The mechanisms by which hydrocephalus develop include:

- Communicating hydrocephalus: decreased absorption of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) secondary to obstruction of arachnoid villi by blood and debris or the development of arachnoiditis

- Obstructive hydrocephalus: obstruction to CSF circulation.

Normal Variants

Common variants are listed in the Table on the left.

LEFT: Coronal image. Cavum septi pellucidi is seen in between the lateral ventricles.RIGHT: Midsagittal image demonstrating a cavum vergae.

LEFT: Coronal image. Cavum septi pellucidi is seen in between the lateral ventricles.RIGHT: Midsagittal image demonstrating a cavum vergae.

Cavum septi pellucidi, cavum vergae and cavum of the velum interpositum

Well known variants are the cavum of the septum pellucidum and the cavum vergae.

The more premature the baby, the more frequently these cavities are present.

They can persist until adulthood.

A less frequently seen variant is the cavum of the velum interpositum.

This presents as a cyst-like structure in the region of the tectum.

It's shape is compared to a helmet.

It can easily be confused with a subarachnoid cyst or a cyst of the pineal gland.

Choroid plexus cyst

In postnatal US these cysts of the chorio?d plexus are often incidental findings without clinical consequences.

Choroid plexus cysts (CPC) are however of importance for obstetricians.

At prenatal US these cysts can be predictive of trisomy 18.

About half of babies with Trisomy 18 show a CPC on ultrasound, but nearly all of these babies will also have other abnormalities on the ultrasound, especially in the heart, hand, and feet.

An exeption must be made for cysts that arise close to the foramen of Monro.

Although these cysts often disappear spontaneously, follow up US is necessary to ensure disappearance.

Some may produce symptoms of raised intracranial pressure due to obstruction to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow.

Benign macrocrania

Benign macrocrania is also known as extraventricular obstructive hydrocephalus.

This is seen in children between 6 months and 2 years.

The head circumference is above the 97th percentile.

After the age of 2 years the head size normalizes.

Often the mother or father of the child had large heads at that age.

The cause is not known. Most state that it is a normal condition, although some state that these children have a slight developmental delay.

When children with a large head are presented for US, examine the superficial subarachnoid space and the ventricles.

The normal subarachnoid space measures less then 3 mm. The ventricles are often slightly enlarged.

These prominent subarachnoid space and ventricular system in these children should not be interpreted as cerebral atrophia, as in atrophia there is a small head circumpherence.

Mineralizing vasculopathy

Mineralizing vasculopathy can be seen in the thalamostriatal and lenticulostriatal arteries and is caused by calcification of the arterial wall.

A wide range of perinatal, acquired, and nonspecific clinical conditions may result in this sonographic finding.

In the Wilhelmina Children's Hospital these children used to be tested for TORCH-infection, but currently the only test that is done is a urine-test for CMV.

Germinolytic cysts

Are located at the caudothalamic groove.

They are tear shaped.

There are no signs of intracerebral hemorrhage and these children have no neurological sequelae.

The etiology is not known.

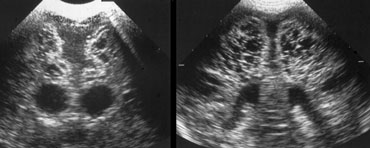

Pseudocyst

These are also called coarctation of the lateral ventricle.

They are often bilaterally and have no neurological sequelae

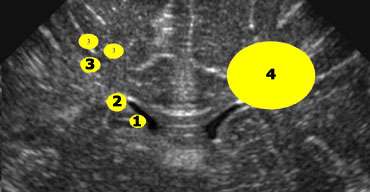

1+2 = germinolytic cysts and pseudocysts, 3 = cystic periventricular leukomalacia, 4 = cysts as a result of a venous infarct

1+2 = germinolytic cysts and pseudocysts, 3 = cystic periventricular leukomalacia, 4 = cysts as a result of a venous infarct

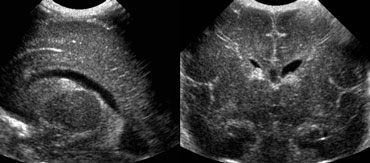

Cysts

If cysts are seen around the lateral ventricles, it is important to determine their position in regard to the upper part of the lateral ventricle (figure).

- 1+2 = Germinolytic cysts and Pseudocysts are below or at the level of the upper part of the lateral ventricle.

- 3 = Cystic periventricular leukomalacia is mostly above this level

- 4 = Cysts as a result of a venous infarct is large and can be either above, at or below this level

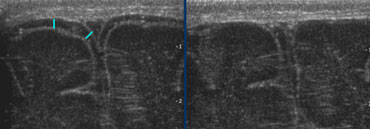

Ventricular measurement

Measurement of the ventricular system should be done in an easy reproducible sonographic plane.

Use a coronal section through the lateral ventricles slightly posterior to the foramen of Monro.

You will see 3 echogenic dots representing the choroid plexus in the lateral ventricles and in the roof of the third ventricle.

Furthermore you should see a symmetrical image of the Sylvian fissure on both sides and the hippocampus (green and orange arrows).

Levene index

Up to 40 weeks of gestational age the Levene-index should be used and after 40 weeks the ventricular index.

The Levene index is the absolute distance between the falx and the lateral wall of the anterior horn in the coronal plane at the level of the third ventricle.

This is performed for the left and right side.

These measurements can be compared to the reference curve and are quite usefull for further follow-up.

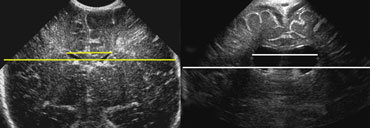

LEFT: Standard measurement of the ventricular index.RIGHT: There is ballooning of the ventricles and the index measurement underestimates the severity of the ventricular widening.

LEFT: Standard measurement of the ventricular index.RIGHT: There is ballooning of the ventricles and the index measurement underestimates the severity of the ventricular widening.

Ventricular index

After 40 weeks the ventricular index or frontal horn ratio should be used, i.e. the ratio of the distance between the lateral sides of the ventricles and the biparietal diameter.

When using this ratio you have to realise, that when the ventricular system widens, the frontal horns tend to enlarge in the craniocaudal direction more than in the left to right dimension.

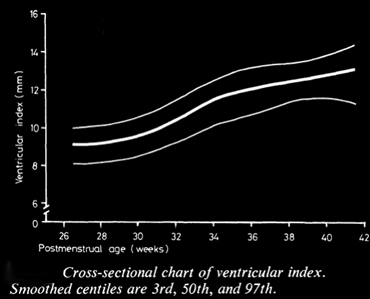

Real-time ultrasound was used to make exact measurements from the lateral wall of the body of the lateral ventricle to the falx (the ventricular index) in 273 infants of varying gestational ages (5).

The measurement performed in an axial plane through the temporoparietal bone correlated closely with an actual measurement made in coronal plane in 50 infants.

A cross-sectional centile chart was drawn up of the normal range for this measurement from 27 to 42 weeks' postmenstrual age.

A further chart showing the rate of change of the ventricular index allowed growth of the ventricles to be assessed in a longitudinal manner.

Use of these charts permits early detection of hydrocephalus or dilated ventricles secondary to cerebral atrophy.

A more realiable indicator of widening of the ventricular system would be an area- or volume-measurement.

This however is more time consuming.

So although ventricular index has shortcommings it is still the most commonly used.

In general practise, studying the images by eye is reliable, provided, that standard planes are used.